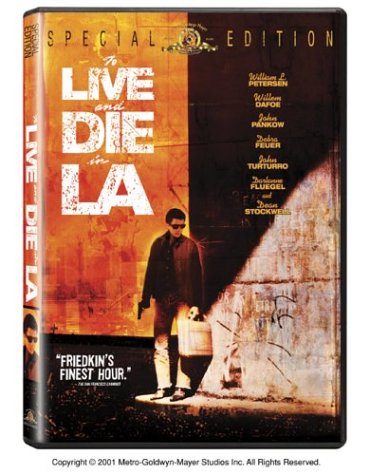

Whether it be the backdrop for a futuristic tale of a world-wearily cop hunting down humanoids or the exploits of a Detroit-based detective who finds his presence extremely unwelcome in one of city’s more affluent areas, it’s a place that has always dealt with the other side to the glitz and glamour it loves to showcase, and this 1986 tale of flamboyant criminals and compromised cops is no exception.

It’s a dazzling story of an arrogant Secret Service man, Richard Chance (William L. Peterson, the year before his role of FBI agent Will Graham in Manhunter) whose determination to bring a master counterfeiter to justice is further exacerbated when his partner is murdered while working on the case. This sets in motion a series of increasingly dangerous and ill-advised attempts to get his man, which see’s Chance not so much straddle the line between right and wrong, as trample on it completely, leaving no evident that it once existed.

Perhaps to be expected with a Hollywood crime thriller from that era, it does have its fair share of well-worn clichés, with one in particular standing out during the pre-credit sequence as Chance’s doomed partner (who is also days away from retirement before he meets his demise) admits to his trusted colleague that he’s “getting too old for this shit”. You half expect Danny Glover to walk into shot and give him a knowing, weary nod.

It’s a misleading opening really, suggesting the scene is being set for a more familiar and formulaic cop thriller. Thankfully, the film has more surprises up its sleeve that that, playing with many of the archetypes found in that genre back then, and very much evident early on in the introduction of the villain, Eric Masters. Played by a young, androgynous-looking Willem Dafoe, Masters is far from your usual Hollywood heavy.

He balances his role of a tough, no-nonsense money launderer with that of a serious, tortured artist, prone to setting alight and destroying his newly produced pieces of art. Dafoe perfectly captures both sides of this complex character, whose actions on paper would probably look a little pretentious and implausible.

Everything you need to know about what drives his criminal career is captured in an incredible montage sequence near the beginning (that showcases some of the blistering electronic score by eighties one-hit wonders Wang Chung) as we follow the exhilarating creation and laundering of counterfeit currency. It’s an early precursor to the now overly-familiar CSI style of throwaway mini-montages, and succeeds here in making this illegal practice look like an art form in itself.

For all the film’s stylistic flourishes, it’s known chiefly (if a little unfairly) for its famous car chase which occurs towards the end of the film, and comes after the disastrous intervention of a sting operation which has been interrupted by the FBI. This chain of events causes Chance (with his new partner in tow and now truly living up to his name), to take drastic measures and force his car into the path of incoming traffic on a busy freeway in a desperate attempt to escape being apprehended.

Having managed to capture what is arguably the greatest car chase on celluloid with 1974’s The French Connection, it’s no surprise here that director William Friedkin was able to pull it off again. It’s a truly gripping sequence which manages to remain pretty feasible throughout and it also acts as a nice reminder that you don’t necessarily need a boatload of digital effects and A-Team-esque logic-defying lunacy to deliver the goods. Its success is derived from a reliance on some incredible in-camera stunt driving, a good spatial awareness of the action, and the audience’s empathy towards Chance’s partner, who by the end of the chase is a whimpering wreck in the back of the car.

Revisiting To Live and Die in L.A recently, I was struck by just how successfully it manages to capture that alternative side to this sprawling city, coming off like a sleazy, pulpier version of Heat, as written by Bret Easton Ellis.

There are no such things as angels here – just a driven lawman whose determination to bring down his prey, no matter what the costs, results in actions which are anything but saintly.

To Live and Die in L.A is available to buy on Region 2. Sadly, the extras from the Region 1 disc (including a fantastic 50 minute retrospective) are missing on the European version.