We are now hip-deep into the Summer Movie Season of 2015. The steady queue of $200m high-concept megamovies lining up to bust blocks between May and the end of August seems to have been a Hollywood tradition since time immemorial. In fact, the entire concept of the Summer Movie Season is only forty years old.

If you wish to send a card or a small gift, the exact date is June 1st 1975. That was the day, four decades ago that Jaws was released in America.

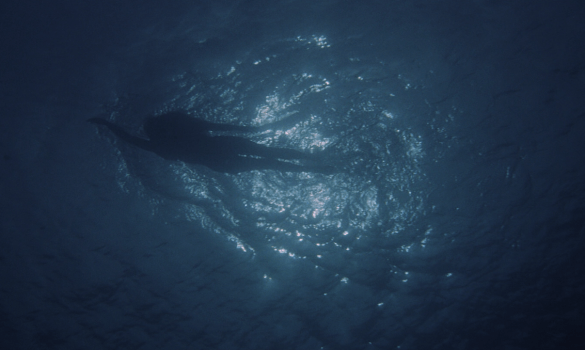

In Hollywood terms, Jaws changed everything and the ripple effects of its explosive debut are still lapping our ankles today. It changed the way movies were advertised and merchandised. It’s has been studied and interpreted as everything from a Marxist treatise, to a metaphor for Vietnam and Watergate and is now accepted to be a modern classic. Furthermore, if it wasn’t for Jaws, you would have had to wait until Christmas to see Jurassic World because before Jaws, there was no such thing as a summer blockbuster.

The original trailer for Jaws from 1975

Blame air-conditioning. Before the use of mechanical room-cooling devices became cost-effective and widespread, the average cinema in July was as fetid and sweaty as a Louisiana toll-booth operator’s arm-pit. Once the sun came out and the schools broke up, the last place on earth anyone wanted to be was at the movies.

Trade reports repeatedly showed that the box office figures took a nose-dive in the summer months, while American and British families packed their towels and headed for the beach. Even the film critics shut their notebooks for the summer – the BBC’s ‘Film’ programme still does, to the puzzlement of just about everyone.

By 1975, cinemas were a slightly more pleasant place to spend a summer’s afternoon. Exhibitors had also noticed that quite a few youth-orientated movies like American Graffiti had attracted a lot of teenagers through the cinema doors in previous summers. Then again, most exhibitors would have had to endure a long wait before the right film eventually found its way into their projection-room.

The practicalities of shipping expensive film canisters around the country meant that release patterns often adopted a ‘Roadshow’ style, with the film touring the country in the same way a rock band would, playing residencies in movie houses like short-run plays. Even The Godfather, at that point the most successful film of all time, only opened in just five theaters in New York before heading out into the wider country to slowly become a box office phenomenon.

Jaws opened in a then staggering 409 North American cinemas and became the biggest movie ever made after only 78 days of release. Universal’s wide-release strategy with Jaws instantly became a Hollywood norm and the numbers (inflated by the arrival of multiplex cinemas in the 1980s) have escalated upwards ever since – Avengers: Age of Ultron, for example opened at 4,276 screens last month.

In the barely imaginable days of No Interet, Video or DVD, movies were very often re-released to maximise sales and cater for repeat business. In Jaws’s case it was rereleased twice (in 1976 and again in 1979). By this point, Jaws had gone from being a hit movie to a global phenomenon and had been spoofed in everything from political cartoons to Saturday Night Live sketches – in the celebrated Land Shark sketch Chevy Chase’s great white stalks young women by knocking on their doors and pretending to be a repairman.

Spielberg himself parodied his own work in 1941, which opened with Jaws’ first victim, Susan Backlinie being terrorised by a Japanese U-Boat to the strains of John Williams’s notorious theme.

Jaws was a critical as well as a commercial success, nominated for four Oscars and winning three – though Spielberg was infamously snubbed; rather rashly filming himself being snubbed (see here). However, the game-changing effect that Jaws had on studio thinking did not please everyone. The studios had never seen such gargantuan sums of money pouring through their accounts so fast – Jaws was the first movie to make over $100m in domestic grosses – but got pretty used to the idea pretty quickly.

This spelled the beginning of the end of the New Hollywood era that had seen the auteur theory become a box office reality with small, independent minded personal films from the likes of Coppola, Friedkin, Bogdonovich, Penn, Altman, Hopper, Scorsese and Pakula enjoying mainstream success. Mass-saturated juggernauts like Jaws and the next phenomenon, Star Wars were blamed for the juvenilization of American cinema which in the eyes of some, has never really grown up since.

Actually, Jaws is fascinating for the way it successfully combines the introspective character-based tradition of New Hollywood with that other 1970s staple: the disaster movie.

An unexpected force of nature arrives out of the blue and places unsuspecting characters in jeopardy and forces them to develop new unplumbed skillsets in order to survive this new reality. Now add to this blueprint either a capsized liner or a burning tower-block, or maybe a pilotless passenger jet, an earthquake-hit city or… a seaside town attacked by a great white shark. All that was missing was Richard Chamberlain in the role of villainous coward.

From the book JAWS: Memories From Martha’s Vineyard

Like most of the great disaster movies of the early 70s Jaws was based on a bestselling but not very good book (the kind of book a murder suspect would be seen reading on an avocado-coloured settee before Lt. Columbo makes an appearance). It was originally conceived along those lines right down to nearly casting Charlton Heston as Chief Brody, and the hiring of a dependable but anodyne director (in this case The Culpepper Cattle Company director Dick Richards, who was let go because he kept referring to the shark as a whale).

It was to the enormous credit of producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown that on the basis of only two films, they saw in 28 year old Steven Spielberg someone who had already proved adept at creating tension, action and suspense (Duel) and also engaging, deeply developed characters (The Sugarland Express). More admirable still was their decision not to use big stars – a trait indelibly associated with 1970s disaster movies – and instead go with a cast made up entirely of character actors.

The acting style in Jaws – low-key, anti-melodramatic realism – is highly redolent of post-Easy Rider New Hollywood, as is the Altmanesque sound design that layers naturalistic dialogue into a documentary-style patchwork – think of the town council meeting after the death of Alex Kintner. The fashionable docu-drama feel is only intensified by the use of location filming, on land and at sea. If it was made in 1965, the Orca scenes would all have been shot in a studio in front of a sea-coloured backdrop and would have looked like the True Love scene from High Society.

Being a film of two halves (before and after they get on board the Orca), Jaws goes from being a disaster movie that might have been produced (but never directed) by Irwin Allen, to a three-way, method acting masterclass that might easily have been written by Paul Schrader. Jaws was released at the precise mid-point of the decade.

The moment Brody slides the curtain across having browbeaten Mayor Vaughn into signing Quint’s cheque, he is bringing the curtain down on the entire disaster movie genre. It’s telling that after Jaws, actual disaster movies seemed immediately ridiculous (well, even more ridiculous) and withered on the vine. The Swarm, Meteor, Avalanche, Airport ’79: The Concorde and the like sounded the death knell until time finally ran out with…um…When Time Ran Out in 1980.

The argument that Jaws’s enormous success also led to the death of idiosyncratic Hollywood cinema has its champions and detractors. If the Summer Movie Season itself is the legacy of Jaws, and thusly the most sensible yardstick against which to measure its achievements, it’s worth trying to list any summer blockbuster since that features characters as memorable, as well written, as sympathetically played and as beautifully counterbalanced as Martin Brody, Quint and Matt Hooper.

With incredible special effects a programmable raison d’être for most prestige epics, remember that Jaws’s biggest special effect was such a disaster in practical terms that it was kept from the screen for most of the film.

It wasn’t the SFX that thrilled us but the characters that we fell in love with and quoted endlessly and mimicked, and still think about whenever we crush an empty drinks can or a paper cup. That, and the fact that every single cast and crew member on Jaws was on top of their game in a collective symbiosis of shared genius they probably weren’t even aware of at the time. It’s why the first Summer Blockbuster is still the best.

In conclusion one has to wonder, how many summer movies from 2015 will we still be talking about and analysing in forty years’ time?