The rarefied summit of the Hollywood A-list is a place that can be extremely hard to conquer. For some who eventually reach those heady heights, they immediately see it as an opportunity to bang the kettle on, put their feet up and take it easy for the remainder of their career at the top, however long that may be.

While some older superstars continually push and test themselves with every subsequent role, even managing to shed their leading performer skin and turn in something akin to a character actor (exhibit A: Tom Hanks in Captain Philips), there are those who continually fail to deliver a performance close to the ones which initially put them on the map and sent them on their ascend.

One of the worst culprits is plane-obsessed Scientologist veteran John Travolta. What’s even more maddening here is the fact that the actor was actually given the rare opportunity of reigniting his career after being stripped of his Hollywood ranking and confined to talking baby films after sleepwalking through a whole slew of post-Grease and Saturday Night Fever roles in the early eighties.

It took superfan Quentin Tarantino to bring the actor back into the public eye in the zeitgeist-capturing Pulp Fiction. And what an incredible performance. There’s something else guiding Travolta here – the most relaxed and unforced he’s ever been on screen, with a dark (yet disarmingly goofy) coolness, rendering an essentially lowlife character completely endearing. He was mesmerising. Get Shorty was next, proving Travolta’s comeback role wasn’t a fluke, and with it, he had firmly staked out his place amongst the A-list once more. It was a glorious time to be alive.

With perhaps the exception of his Clinton-esque turn in Primary Colors, the fine character work in both of those comeback roles is conspicuously missing from any of his post-Shorty films: Michael, Battlefield Earth, Domestic Disturbance, Lucky Numbers, Swordfish, Basic, The Punisher (in which he playing the least intimidating villain in cinematic history), Old Dogs, Be Cool, From Paris with Love, Savages. The list goes on and on.

The man who once tripped the light fantastic with fellow career-slider Uma Thurman has now been reduced to having an animatronic crow crash into his visor as he desperately hams it up to contemptible levels (Wild Hogs). Amazingly, his workflow remains steady. Maybe devoting your life to those thetans in the sky is the key to career longevity?

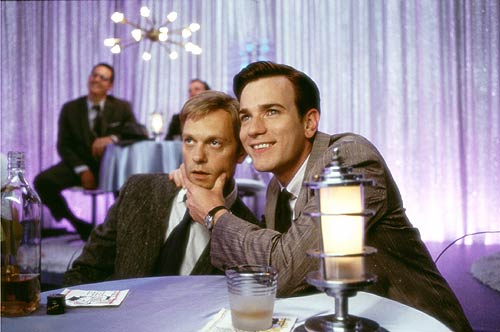

While never coasting as badly as Travolta has, Ewan McGregor has delivered largely passable, unadventurous turns in a number of middle-of-the-road Hollywood fare of late. He’s done brooding (Young Adam) and lovelorn (Moulin Rouge) pretty well, but the wired and jittery urgency of smack-head Mark ‘Rent-boy’ Renton in Trainspotting, a truly spell-binding turn by the actor, has never been replicated.

Watching McGregor perform and it’s almost like there’s an invisible barrier in front, where he won’t allow himself to channel that exposed and captivatingly authentic side once more.

An absolute revelation as real-life career criminal and affable sociopath Brandon Read in Chopper, Aussie import Eric Bana was given the access to the hallowed halls of Tinseltown soon after, but was completely anodyne and bloodless in the likes of Troy and Ang Lee’s much maligned Hulk. Offering up a decent if unremarkable turn in Spielberg’s much underrated Munich, his villain in the 2009 Star Trek reboot was merely perfunctory, bringing only a smidgen of that searing and volatile menace from his debut.

Given that he entered the industry as a much-loved stand-up and small screen comedy star in his native country, it’s interesting that Bana has rarely chosen to flex those muscles in his US work. He was gregarious, funny and humanly flawed as Leslie Mann’s meat-headed Aussie Rules Football obsessed husband in Judd Apatow’s Funny People, not having to be straight-jacketed by putting on an accent, and essentially letting shades of his own persona through. He needs to channel that again, and soon.

Nepotism in Hollywood will only get you so far before you actually need to really put the effort in and prove yourself. Kate Hudson appears to have engineered that journey in reverse. Captivating and vulnerable as ‘band-aid’ Penny Lane in Cameron Crowe’s rich paean to his youth, Almost Famous, Hudson’s subsequent Oscar nomination for the role not only went straight to her head but apparently signalled to her that she could take it easy now as the grunt work was over.

15 years later and turn after turn in some the most lacklustre romcoms ever to have graced modern cinema screens, life on the road with Stillwater seems so very far away.

Where to start with Charlie Sheen? Giving a deeply heartfelt and sensitive performance as Oliver Stone’s surrogate in the director’s first ‘Nam opus Platoon, almost thirty years later, Sheen has never delivered anything close to that kind of performance again, and has made a virtue out of just how little he can get away with doing on set, whilst raking it in.

Although he may not be counted amongst the A-list anymore in terms of a big screen career, the $1.8 million he earned per episode for Two and a Half Man (every performance from that show is an abject lesson in how to do zero for a stinking wad of cash) was certainly equal in comparison to the going rates of many a movie star’s salary. Even an intriguing attempt at a meta reappraisal of his life in 2012’s A Glimpse Inside the Mind of Charles Swan III failed to bring out the requisite depth and shading from Sheen.

Perhaps this kind of half-hearted activity is synonymous with any industry. We’ve seen colleagues who are happy to do as little as humanly possibly while they eagerly await their next payslip. Should we expect employment in Hollywood to be any different? Well, yes. The very nature of putting themselves on display means these performers can’t have a quick snooze in the work toilets, or talk their colleague into delivering the bulk of tomorrow’s board presentation. They have to be engaging and present at all times.

A mix of ego, misdirection and reluctance to stray from the comfort zone could all be contributing factors here, and since these performers are being paid handsomely for each project, why should they feel the need to go out on a limb if that isn’t what’s being asked of them? An opposite figure to the Travolta’s of the world is an actor like Brad Pitt.

Breaking through in Ridley Scott’s Thelma and Louise way back in 1991, for the most part, it’s clear the actor has gained the confident to really develop his craft in the last couple of decades. This could be in largely due to the singular, auteurial filmmakers whom Pitt has aligned himself with. When you’re starring down the lens of a David Fincher, Alejandro González Iñárritu or Andrew Dominik production, there’s little room to amble along and hope for the best.

But in the cushy realms of mainstream Hollywood, some are obviously disinterested in career progression or spreading their creative wings. That’s their prerogative of course, but sooner or later, audience indifference will strike, and by then they may have wished they’d pestered their agent for that impromptu meeting with Alfonso Cuarón or David Gordon Green.