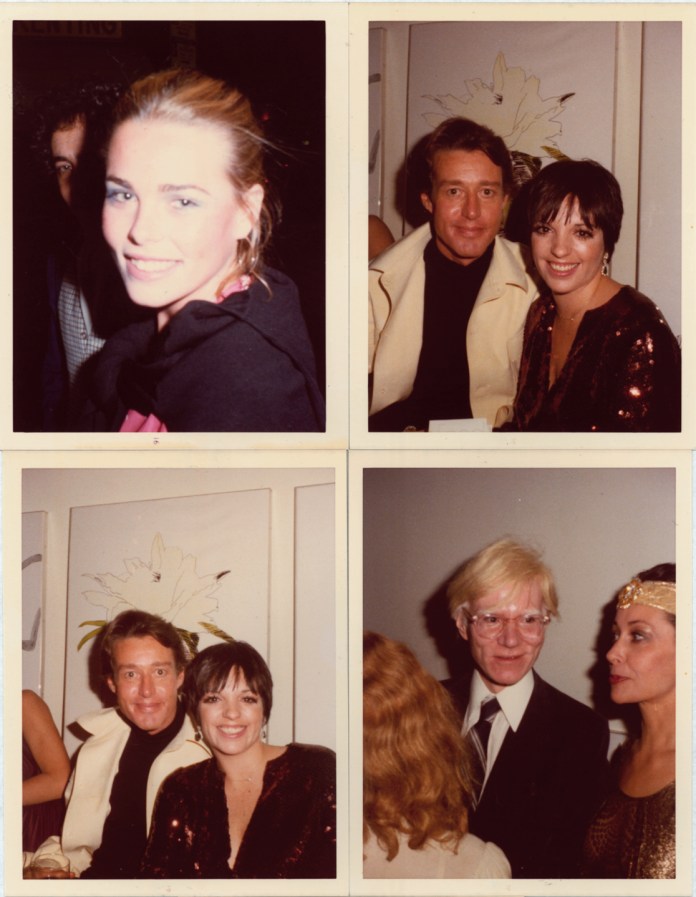

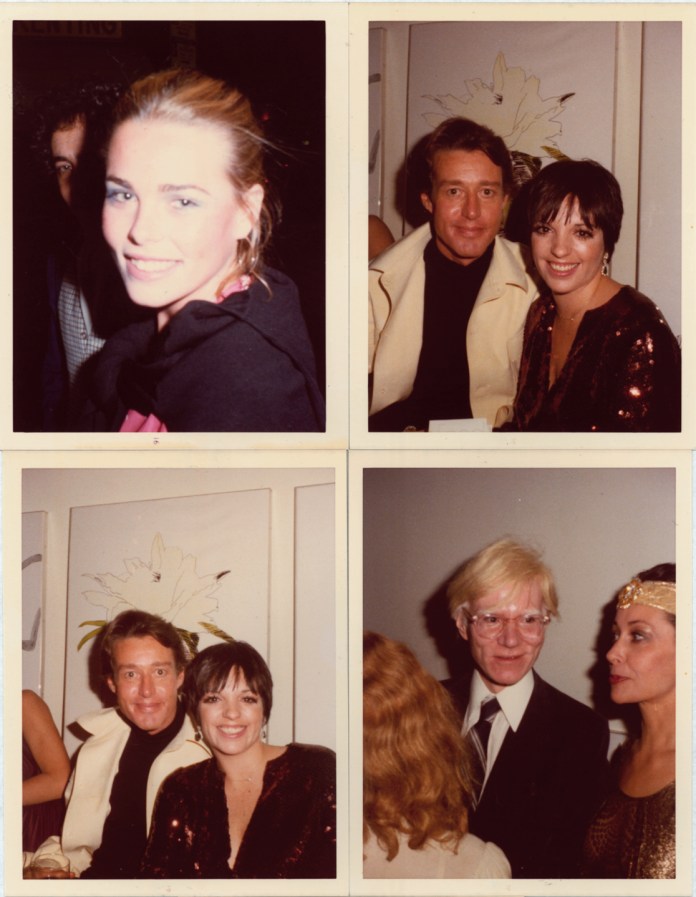

James Crump’s new film Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco is a fascinating portrait of fashion illustrator Lopez, his partner Juan Ramos, and their creative milieu in late 1960s and early ‘70s New York and Paris. Lopez is credited with discovering many of the women whom he surrounded himself with as muses and friends such as Grace Jones, Pat Cleveland, Jessica Lange, Jerry Hall and Warhol Superstars Donna Jordan and Jane Forth, regarded as unconventional beauties by the style arbiters of the time.

The film explores the blurred lines between Lopez’s personal and creative lives, his process of working and his relationships with prominent fashion and art figures such as Andy Warhol and Karl Lagerfeld. There are compelling and often intimate insights from those who knew Lopez well including American Vogue’s Grace Coddington and Oscar-winning actress Jessica Lange, with a poignant final interview from the late iconic New York street and society photographer Bill Cunningham. It’s an absorbing watch that examines and celebrates a life cut far too short by AIDS and makes a persuasive case for Lopez’s continuing significance in fashion.

Ahead of the film’s US theatrical release, James Kleinmann spoke to director and producer James Crump for HeyUGuys in New York.

James Kleinmann: One of the things I enjoyed about the film was that I really felt like I wanted to hang out with these people and get to know them and just go back to that time and place. The film allowed me to do that. I wondered how much you felt like that as you went about making the film and how intentional it was to create that kind of feeling in the audience?

James Crump: When I started making the film what I envisioned from the very beginning was to make a time capsule. I wanted the viewer to be transported back in time to that early Seventies period because it was so exciting for me, learning about Antonio over the years and gathering stories. I also felt that the period was this bygone era that will never be created again. It was a brief moment of real attainability, real freedom where the things that had been fought for in the cultural battles of the late Sixties were starting to manifest. Some people have said it’s a moment of innocence and I don’t know if that’s accurate, but it is a moment where things are coming together, like gay rights, women’s rights, civil rights and the anti-war movement. All these things in the early Seventies are coming together and there’s a sense that things are changing.

There’s a real revolutionary sense of change and this is maybe seven or eight years before the dark cloud of AIDS is starting to hover in the distance. Things get much darker as the Seventies wear on, with addiction and overindulgence and so forth and so it’s this kind of moment where there’s freedom, there’s liberty and there’s a sense of attainability. Antonio for me was this person who was emblematic of that, he underscored the sensibility of that moment and that’s what he’s about. He’s this person who wanted to work freely, without restrictions, he doesn’t want to be told what to do, he wants to create his own life, his own aesthetics, his own vision and he wants to do it with the kind of people he’s drawn to. That was all part of why I wanted to make not a documentary, but rather a time capsule.

I don’t use that word – ‘documentary’, it’s a piece of cinema that is transportive and immersive. I love it when people can see it on a big screen because it is really immersive and they can kind of drop out for an hour and a half.

Why don’t you use the word ‘documentary’? Is that just in relation to your own work?

I think it’s a fraught term, it conjures up a lot of anachronistic ideas about filmmaking and I want to make a beautiful, original motion picture that traffics in cinema that can be seen alongside other kinds of film. The word makes you think about a person strapping a camera on their back and just walking around and recording things. Today making these kinds of non-fiction films it’s more of an art form, there are more tools at our disposal so it’s not the same as say it was in 1960 making a film that’s nonfiction.

Certainly, I can really see that in the way you use Antonio’s illustrations beautifully in the film. Can you talk about that aspect, deciding on which illustrations to include and the way you’ve chosen to present them; they’re dynamic, you kind of animate them, we see them get coloured and there’s movement in them.

It was challenging to choose the illustrations because I wanted to stick very closely to the time period of 1968 to ’73, so I chose illustrations that fitted into that timeframe, but not too rigidly. If I saw a picture from the Eighties that was incredibly sexy I’d put it in if I was really drawn to it. I’m an art historian by training and I have a great deal of respect for artists and for the preservation of art and so forth, so I wanted to do something with the illustrations that would make them come to life.

Fortunately I came into contact with a special effects person who works at a major studio who happened to start off his career as an illustrator who really understood what I was getting at. Together we found this really nice balance in colourisation and movement without being too heavy handed with the actual analogue, 2D pieces. So I’m happy with that and I think everyone who’s involved with the archive is very pleased with how it turned out visually.

In terms of the archive, how open were they to you gaining access to Antonio Lopez’s work and how challenging was it to decide what to use in the film?

With my previous films I’ve had real challenges with foundations, with the representatives of deceased artists, people who want to control the trajectory of their legacy. In this situation it was entirely different, I had already met Paul Caranicas who’s in the film, he was Juan Ramos’ lover until Juan passed away of AIDS. When I first met Paul over twenty years ago, basically he just gave me carte blanche, he just let me have complete freedom to spend time in the archives going through thousands of drawings and photographs. He prepared transfer files of all the film materials and I just felt so fortunate and so privileged to have that access. He told me a few years ago that I was the first person to come knocking on the door and then a wave of people came subsequently.

I didn’t really start thinking of it in terms of a motion picture until about four or five years ago, it just seemed right, it seemed like the story had been resonating with me for a really long time, as with the other films I’ve made, and it felt like the time was right, let’s do this film right now. And I think it arrives with some unexpected urgency because of what’s happening in fashion right now. If you read any of the journalism about fashion today, even this week during New York fashion week, it’s a moment of change and revolution in terms of diversity on the runway, inclusivity, a rise of subcultures with major fashion designers at the forefront with their entourages making major changes with how we receive fashion, what fashion actually means, the definition. But it has to do with this embrace of otherness and inclusivity and diversity and those were things that Antonio was completely about in the late Sixties.

To me what drew me to him originally was that I found that he had this kind of prescient vision that was almost paranormal and that’s alluded to in the movie where he would really look at a person individually and he would in a way see inside of them and find things in them that maybe they weren’t seeing about themselves. This person who was completely open to otherness, to individuality, he was also in a way kind of disrupting classical notions of beauty that were lingering after the post-war period and that’s happening right now too.

We’re having this disruptive moment where types of beauty, classical notions of beauty, institutionalised notions of beauty are being completely exploded by this wave of colour, this wave of model spokespeople of colour and the kind of street aesthetics that are coming into play in fashion. That was something that Antionio completely embraced which went hand in hand with the devolution of haute couture to ready to wear. So we’re kind of back in a revolutionary moment, so to me the film has landed with an unexpected urgency and a relevancy that I didn’t initially expect, but I like that, I like it very much.

Can we talk a bit about some of the contributors. There are some brilliant interviews in the film. One that I particularly enjoyed was Bill Cunningham’s interview, he’s smiling and laughing so much as he reminisces about his friends, but then he’s also in tears, very emotional at times; it’s just a wonderful interview. When you were conducting it did you realise that it would form an important part of the film?

I knew Bill’s history with Antonio pretty well, but there were a lot of things that came out of the interview that I hadn’t expected. Firstly, we know a lot more about Bill since he passed away, there’s a new memoir that was recently published for instance. He was a very modest person, we actually think of him more in terms of a Gandhi like character because he lived so modestly. He wasn’t a material person, he was just very understated, almost self-effacing and that he came to the interview at the New York Times building so forthcoming and so open, I think really speaks to how much Antonio and Juan meant to him. It must’ve meant a lot to him that Antonio and Juan’s story be told because he was just so sharing and really came with enthusiasm and just a benevolence and blessed the project in a way. It was his last interview before he passed away and I sense looking back that he probably knew that his time left on Earth was short and this was his chance to share these stories. So that was a really incredible moment and also very emotional as you can imagine. He did break down a few times and we had to turn the cameras off. We were all sobbing, a crew of six people and we had to take a break a couple of times. When we think about Bill we get emotional because you could tell there was a lot of love coming out, just seeping out, just this incredible sense of love towards these guys. I think he really adored them and considered them his best friends.

The story that Bill Cunningham shares about Karl Lagerfeld turning down Antonio’s request for work when he was ill with AIDS and needed money is impactful. Were you ever in two minds about whether or not to include it?

I wasn’t aware of that story before. I’d heard some things like it, but not defined in that way. We cut the ending of the film, that part of it many times, like five or six times and especially the part where Bill breaks down emotionally because I didn’t want it to be exploitative at all. I didn’t want to take a cheap shot because the film had come so far, but if you get that wrong it might possibly be offensive, it might not be true to how Bill really was, so we cut it very sensitively. I felt at one point that the Lagerfeld story may or may not fit in, but in the end I thought it was very poignant and it was this notion that someone who shared so many intimate moments with Antonio and had worked very closely with Antonio would turn his back at the end of his life when he was really in need of help. That to me was shocking and it was just profoundly saddening.

I just felt like it worked in the cut and I gave Karl Lagerfeld an opportunity to be part of the film and he chose not to be. I met him almost twenty years ago. I hand delivered a handwritten note to his assistant in Paris and I also followed up and he was completely silent and apparently didn’t want to participate. He’s got a lot going on, but I did give him an opportunity. I would have enjoyed having a conversation with him. That could have been a really interesting piece of cinematic tension. But Bill Cunningham is not given to fabrication or lying or to deceiving, he’s a very straight shooting person and so I take Bill at his word completely because he has no reason to fabricate.

Was there anyone else who you would’ve liked to have spoken to for the film who you didn’t get? I imagine Jerry Hall might’ve been someone you approached.

Jerry Hall I did approach as well and early on she was very keen to participate and as we started producing the film all of a sudden she got married to Rupert Murdoch and communications desisted. But when I look back at it I’m really pleased that she’s represented like Karl Lagerfeld is represented in the film. I think it worked out in a very beautiful way and I think the proper way. They help you stay inside that time capsule because you’re seeing Karl Lagerfeld in this very butch, buffed out way in his early thirties and you’re seeing Jerry as a teenager and then there’s these incredible intimate moments, some celluloid, amazing moments. I think looking back on it, maybe it would’ve been a bit more jarring to have Jerry Hall for instance in the film as she is right now with Rupert Murdoch, it just seems so antipodal to what the film’s story is about and where she is now compared to where she was then. I think it’s a blessing how it worked out. I didn’t plan it that way of course, you try to get people to participate, but in the end it was a blessing in disguise, that’s how I feel about it.

You did speak to Jessica Lange and there’s a wonderful interview with her in the film, I loved it when she said she had a ‘wild crush’ on Antonio. You can she that she’s really transported back to that time in her life as she speaks, it was clearly a formative, significant period for her.

I think Jessica does a really wonderful job of articulating some of the things that fascinated me most about the period; the sense of freedom and this more libertine time where anything was possible and it’s very clear that she was completely in love with Antonio. As a filmmaker, as a director, a producer, you’re going for some cinematic tension. You want diverse stories, you don’t want everybody to say the same things and you choose your subjects very carefully in hopes that you get this contrast and sometimes you even get some contradiction and things like that to play with. I’ve received criticism saying that this is just a positive story, there’s nothing abhorrent or negative, but I think Antonio comes through as a human character, he’s also fallible.

There’s a part of the film that describes what today some might call sexual addiction, that’s how some have described it and Antonio’s narcissistic needs, he was incredibly in need of attention and he sometimes got physical with Juan. They had an incredible collaborative partnership, but it wasn’t free of any discord, you know that’s part of the fuel that makes a collaboration like that work, sometimes you don’t agree. As Paul Caranicas says in the movie, it’s either going to end up in a drawing or a fist fight. So Antonio is not perfect, but I think he touched people in a way that’s so genuine and because I had this experience interviewing these people you go prepared, you go to ask the right questions and their emoting and getting very emotional and it’s real. That’s the story and maybe the story is just about love.

People were genuinely touched almost in a paranormal way, he had this ability, this magnetic quality that got inside them and people really connected with him. And maybe it was at first erotic, but then it was spiritual or emotional or true friendship, and it comes through in the interviews I think. But again it wasn’t something I had planned out, you never know how a film like this is going to turn out until you’re in the final stages of post-production, that’s what’s magical about making a film like this.

One of the fascinating things about the film is getting to see how Antonio Lopez’s life cross-sectioned with so many other significant figures. Someone we haven’t discussed yet is Andy Warhol.

I think how it’s presented in the film is very interesting. Warhol was someone who was very influential to Antonio and someone Antonio looked up to, but there was a productive rivalry as well. That Warhol started off as an illustrator was not overlooked by Antonio, they became friends and mutually competitive, but also mutually supportive characters in each other’s lives. I think had Antonio lived longer he would’ve attempted to, in fact he was already attempting to, transcend the limitations of simply being an illustrator. I don’t consider him as simply an illustrator, he’s a stylist really first and foremost, he made collections, he did campaigns, he wasn’t just this thing called an illustrator. He was also using motion picture cameras, he was using the Instamatic, he was using Polaroid and I think had he lived longer he would have tried to do something more along the lines of a supernova like Warhol, just rack it open and be part of a larger spectrum of “capital A art”.

He would have been perfectly at home today because I think some of the things he was doing were so prototypical, like the notion of turning the cameras on yourself diaristically and recording your life in a very narcissistic way and your friends, and your entourage and your social habits and that’s what’s happening right now on social media, that’s what we do on our devices every day. The designers who are appropriating his aesthetics or in some cases using designs in their own collections like the Kenzo designers Humberto Leon and Carol Lim or Jeremy Scott or the many others who are really very influenced by Antonio Lopez, they’re using social media in their practices in very intelligent, creative and to some extent provocative ways too, and I think Antonio would’ve been rather at home right now at this moment.

Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco opens in New York at the IFC Center on Friday 14th September 2018 and will expand to other US cities, for more information visit the film’s official website. There will be Q&As with James Crump and other guests at the IFC Center on Friday 14th and Saturday 15th following the 8:20pm screenings.