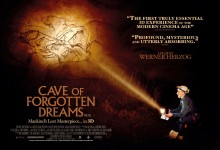

In the Chauvet Cave Herzog has found an incredibly fascinating subject for this film and it is not long before he immediately bends the subject, absorbing it into a discussion of his own preoccupations and obsessions. The Cave is filled with examples of early man seemingly expressing himself through art and with Herzog as our guide through this prehistoric gallery the paintings are transformed into glimpses at dreams and examples of a special kind of early cinema. These links, whilst occasionally a little tenuous, open up the subject, sending ones mind in interesting directions and ensuring we experience the paintings through Herzog’s unique viewpoint.

The way in which Herzog chooses to frame the paintings with his 3D cameras also adds to the experience greatly and a simple pan across one of the cave walls feels as majestic and beautiful as the opening of Aguirre, Wrath of God or the ship ascending the mountain in Fitzcarraldo. His use of this stereoscopic tool complements the contours of the painting’s canvases, the cave walls, and also mirrors the way in which the painters used the physical spaces to accentuate their paintings.

Whilst the application of 3D in the caves is effective and fascinating there are other times in which it is merely used as a gimmick or worse, actually abused. In one particular sequence an experimental archaeologist is interviewed and shares his thoughts on the kinds of weaponry that the painters may have used. Cue shots of the archaeologist throwing spears at the camera, putting one in mind more of the 1950s Columbia 3D westerns than of a serious application of stereoscopic techniques by a skilled filmmaker such as Werner Herzog.

The most egregious use of 3D though is in a sequence that begins with a camera attached to a radio controlled flying vehicle. Slowly the vehicle descends towards a group of people in what is actually an oddly beautiful shot. Very quickly though two seemingly giant hands reach out to grab the vehicle and the dissonance in the 3D causes a pain in ones eyes and the desire to throw the glasses across the room. Both of these examples though could very well merely be examples of Herzog’s notoriously oddball sense of humour and actually less than subtle digs at the application of 3D technology by other filmmakers.

The film unfortunately suffers whenever Herzog steps outside of the cave and the talking heads featured lack the great character and amusing tangents that helped make Herzog’s previous doc, Encounters at the End of the World, so compelling. They are far from dull though and Herzog’s dogged persistence to get those he interviews to speculate about questions such as dreaming certainly make them entertaining in places. These interviews also add to the discussion that Herzog begins with his thoughts on the paintings and surrounds this tipping point when early man became human, possibly expressing himself/herself through art and documenting the present for the future. Returning to this idea in a bizarre but uniquely Herzogian postscript the film fittingly closes on Herzog exploring concepts of humanity through his own animal centred artistic expressions. Occasionally frustrating and unfocused but always fascinating and compelling, Cave of Forgotten Dreams is an utterly mesmerising documentary.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams is released in UK cinemas on the 25th of March.

[Rating:4/5]