With the third season of The Trip soon upon us, before witnessing Steve Coogan dine with Rob Brydon across a beautiful Spanish landscape, we can see the British actor indulging in fine cuisine of another kind, this time with a somewhat more bitter aftertaste, for he takes the lead role in Oren Moverman’s dark and disturbing thriller The Dinner, based on Herman Koch’s novel of the same name, which proves to be a film stifled by its very own sense of ambition.

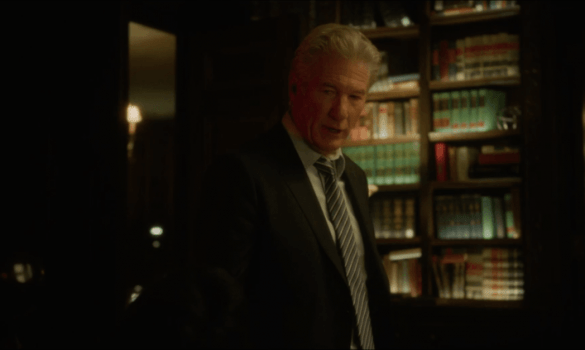

Coogan plays Paul Lohman, a school teacher doing all he can to avoid going out for dinner with older brother, and congressman Stan (Richard Gere), and his wife Katelyn (Rebecca Hall). But Paul is persuaded by his own wife Claire (Laura Linney) who is rather insistent they make the trip, and as they set food in the grandiose, pretentious restaurant, it becomes clear why, as they have a rather pressing conversation to have concerning their sons – determining just how far parents will go to protect their offspring.

Though initially Coogan appears to be channelling his inner Woody Allen, neurotic, paranoid and prone to the occasional zinger – it’s when we begin to fully understand this character and his background when the actor truly comes into his element, surprisingly when the comic tendencies are put to the side and he’s reliant more so on his dramatic capabilities, proving to any potential casting directors that he’s more than able to play nuanced, substantial roles of this nature. Regrettably, however, it’s a performance that is better than film its placed within, which attempts to cover too much ground, overwritten and overlong.

There are similarities to be made to Danish production Festen, in how we’re delving into a demented series of events concerning a family, which thrives in the sub-text, and what’s not said. But the Dogme endeavour knew what it was, it had a core narrative and the characters, and intersecting plot-lines orbited around that. Moverman deviates so carelessly away, and we find ourselves going down tangents that do nothing but distract us from what’s important, such as the film’s most bizarre, superfluous sequence taking place at a war memorial. There is no denying there is a really good film in here, it’s just one that has suffers greatly from its needlessly convoluted approach.

There are similarities to be made to Danish production Festen, in how we’re delving into a demented series of events concerning a family, which thrives in the sub-text, and what’s not said. But the Dogme endeavour knew what it was, it had a core narrative and the characters, and intersecting plot-lines orbited around that. Moverman deviates so carelessly away, and we find ourselves going down tangents that do nothing but distract us from what’s important, such as the film’s most bizarre, superfluous sequence taking place at a war memorial. There is no denying there is a really good film in here, it’s just one that has suffers greatly from its needlessly convoluted approach.

It doesn’t help matters that nobody is particularly likeable, and while that’s far from being a prerequisite in cinema, as some of the finest antiheroes that have graced the screen have been immensely flawed, but it’s jarring on this occasion, as you need a horse in this race, somebody to invest in emotionally. But the writing isn’t accomplished enough for this to be the case, and the lack of empathy is detrimental. It’s the screenplay which proves to be the film’s greatest undoing, for the performances can’t really be faulted. Even just the contrived way the characters refer to each other by their family connection, “Hi brother”, or “Sorry cousin” – a pedantic criticism, perhaps, but people do not converse in this way, and it’s emblematic of a film that, while striving for realism, seems unwittingly inclined to avoid it.