The first full-length film from celebrated Senegalese film director Ousmane Sembène, Mandabi (The Money Order) was met with international acclaim back when it was released in 1968 and has only grown in stature throughout the ensuing years, picking up one particularly high-profile fan in the form Martin Scorsese, who has described the film as his gateway to African cinema. His passionate response to the film is, unsurprisingly, entirely justified. Like many great world cinema titles, it offers a window to another culture seemingly far-removed from the viewer’s own. Yet scratch under the surface, and it’s very apparent that the same issues and those very human foibles exist on a macro level.

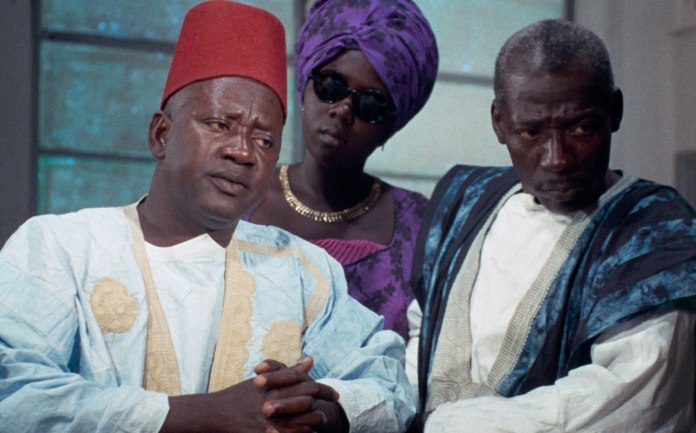

We are introduced to the film’s protagonist Ibrahima (Makhourédia Guèye) as he’s receiving a groom and shave in the film’s opening credits. Returning to his threadbare home, he leisurely guzzles down huge amounts of prepared food, praising God as he wallows in his gluttony, giving himself supreme indigestion in the process. Both are rather luxurious treats for a man in lives in near-destitute conditions with his two subservient (but impassioned) wives and seven children. Possible financial salvation comes his way out of blue when his Paris-based nephew Abdou sends him a money order worth 25,000 francs, the majority of which is intended to be safeguarded by Ibrahima with a decent wedge put aside for him in return for his efforts.

We are introduced to the film’s protagonist Ibrahima (Makhourédia Guèye) as he’s receiving a groom and shave in the film’s opening credits. Returning to his threadbare home, he leisurely guzzles down huge amounts of prepared food, praising God as he wallows in his gluttony, giving himself supreme indigestion in the process. Both are rather luxurious treats for a man in lives in near-destitute conditions with his two subservient (but impassioned) wives and seven children. Possible financial salvation comes his way out of blue when his Paris-based nephew Abdou sends him a money order worth 25,000 francs, the majority of which is intended to be safeguarded by Ibrahima with a decent wedge put aside for him in return for his efforts.

It isn’t long before seemingly the entire neighbourhood catch whiff of Ibrahima’s good fortune and he’s soon having to contend with every hanger-on, scammer and emotionally manipulative villager, desperate for a piece of the pie. But Ibrahima is ill-equipped to handle his new-found windfall. Devoid of any ID to release the funds – a birth certificate is a no-no as he’s unable to even confirm his year of birth – he starts buying items on credit, pawning anything remotely valuable he can get his hands on and borrows what he can against his incoming cash in an attempt to get around the bureaucratic obstacles in his way.

In large part, Mandabi oscillates between stinging satire and sobering social commentary, both brought together by Guèye’s subtly humorous and deeply expressive performance. Ibrahima is a selfish, contradictory figure, his billowing blue robe always getting the better of him as he bumbles around from one incident to the next while fighting to stay afloat until the money comes in (it would be of zero surprise if the Safdie brothers had seen and gained an appreciation of this film in their formative cineaste years). Sembène gets some surprisingly committed and convincing turns from what appears to be largely non-professional cast, and his film at times has an appealing ambling Antonioni-feel to it as we’re transported back and forth between the vaguely metropolitan Dakar cityscape and the dusty, poverty-stricken outskirts.