David Oelhoffen has made only one feature prior to this Algerian tale but he has achieved one of the Venice Film Festival highlights so far.

Based on an Albert Camus short story, The Guest, the film is about reclusive schoolteacher Daru (Viggo Mortensen), born in Algeria to Spanish parents, and the year is 1954 at the onset of the Algerian War. Daru’s school is in the midst of rural Algeria, but the rebellion soon begins to encroach even in this far-flung place. One night Daru is asked to take a prisoner, Mohamed (Reda Kateb), to the authorities in Tiglit. Before they leave, they are ambushed twice, once by the family of the man Mohamed killed, and later by a local French settler who is looking for someone to blame for the slaughter of his livestock. As they head off they face the threat of running into rebels, soldiers and brigands on their journey.

It transpires that Daru is no ordinary schoolteacher, but once served four years in the army. Yet as he sees the atrocities perpetrated by the men whose uniform he once wore, he can no longer associate himself with his past.

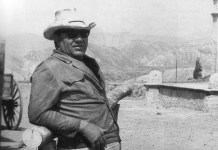

Oelhoffen has made recourse to the traditional western for this film: we have a solitary hero who has hung up his weapon only to find he has to take it up again; there is the unlikely friendship between the lawman and his prisoner; and we even have a dusty town containing a saloon replete with swinging doors and whores for hire. The North African landscape is also like that of a classic western, with arid and scorching landscapes that can turn bitterly cold in winter. Yet there is also something of Lawrence of Arabia, with the sweeping vistas of the Atlas Mountains (the film was actually made on the Moroccan side of the mountains) and men riding through the harsh valleys on Arabian stallions.

The director has managed to take Camus’ story, fill it with a more complex political backstory that is very much part of today’s news as we view the consequences of Western intervention in other parts of north Africa, but he has also made a classic western. And it is not just Daru who is the complex hero: Mohamed’s reasons for killing his cousin were to save his family, yet he now realises that this means his cousins will have to kill him, in turn requiring his little brothers to kill a cousin and so on in a bloody downward spiral. The only way out of this is to hand himself over to the authorities and let them be responsible for his death, thus nipping in the bud the inevitable family slayings. What Daru has to do is find a way of saving Mohamed and keeping himself alive.

Kateb and Mortensen put in utterly convincing performances, the latter showing that he can act in about five different languages. With Nick Cave’s atmospheric score added to the stunning visuals, David Oelhoffen’s adaptation is a beautiful and stirring masterpiece.